Getting started with

Peer Observation

What is peer observation?

Peer observation is when a teacher observes another teacher in order to develop their classroom practice. A peer can be any colleague willing to support you. They may be from a different department or year team, have recently joined teaching, or be a member of the senior leadership team. Peer observation is a two-way process that can benefit both the observer and the teacher being observed, with the goal of improving learning and teaching.

"…the defining characteristic of this model is the importance of the one-to-one relationship, generally between two teachers, which is designed to support Continued Professional Development (CPD)."

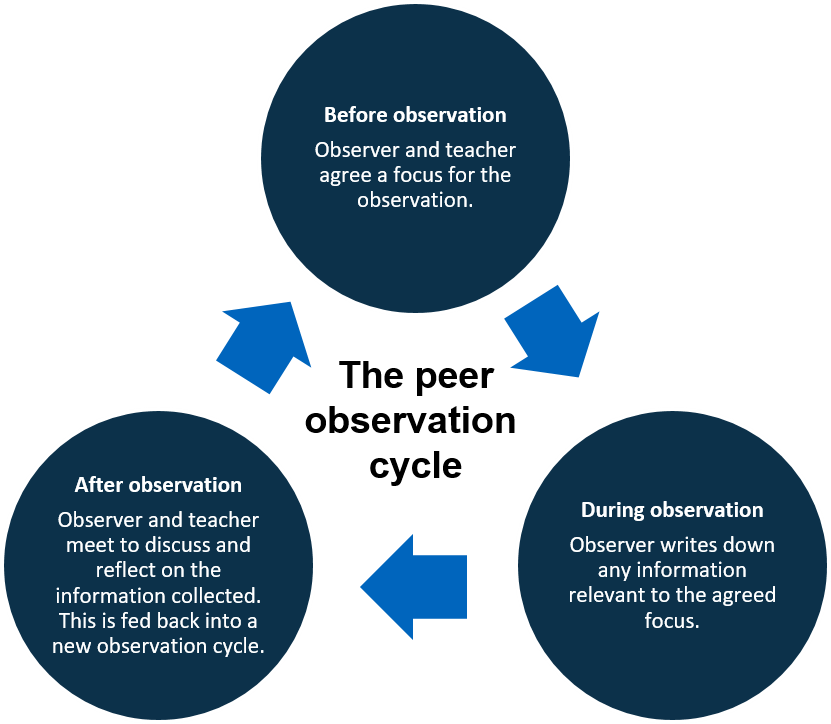

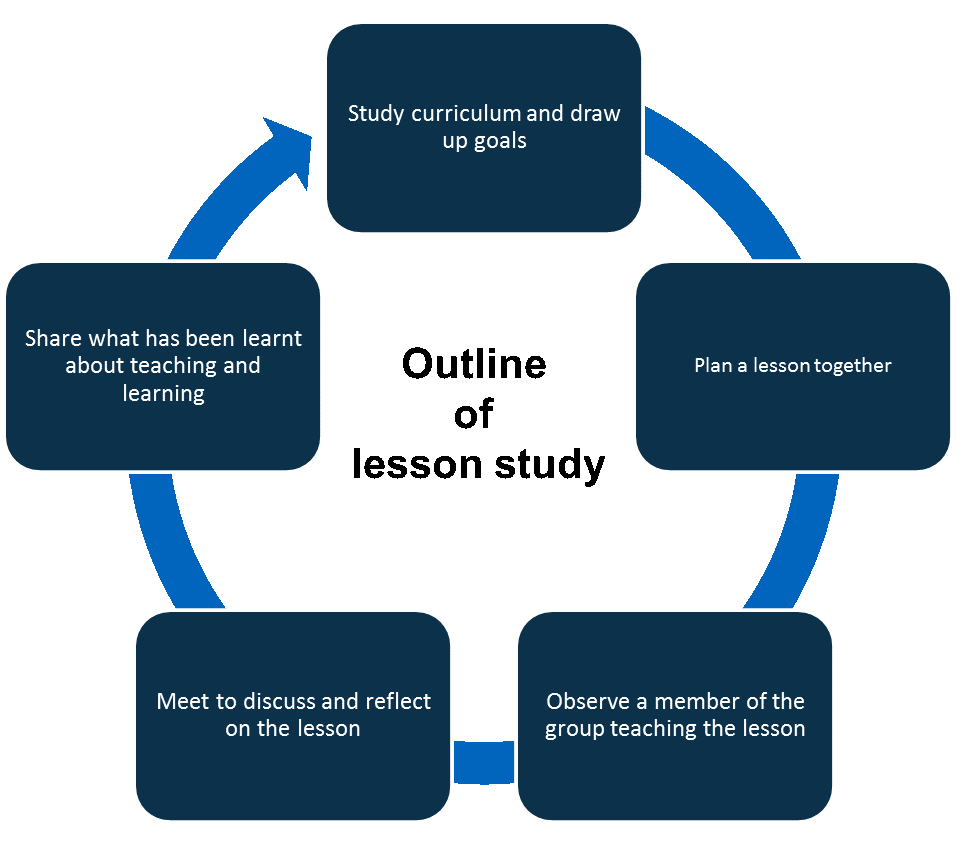

Effective schools appreciate that non-judgemental observations can form part of high-quality professional development. These schools see peer observation as important because it can improve the quality of teaching and learning for an individual and a whole school. The diagram, adapted from ‘Classroom Observation’ by Matt O’Leary (2014), is a typical model of how peer observation works.

In the rest of this guide we will look at each stage of this cycle in more detail. There will be opportunities for you to reflect on how peer observation might support your professional development and the continued professional development (CPD) offered in your school. Also, we will look at the common misconceptions about peer observation and look at peer observation in practice. We have provided a glossary of key words and phrases at the end of the guide with suggested further reading in the ‘Want to know more?’ section.

What are the benefits of peer observation?

Benefits for the teacher being observed

Peer observation works alongside other forms of professional development.

Peer observation gives you an opportunity to apply what you have learned from other forms of professional development, such as conferences, training courses or reading. For example, after attending a training event where a new learning strategy was introduced, you could use peer observation to get constructive feedback on how this strategy would work in your situation.

Peer observation encourages honest conversation.

It is essential that the observation is used to gather evidence to encourage a constructive and supportive feedback conversation. At no point should you be judged. Without fear of being judged you may want to focus on how particular groups of students responded to stages of the lesson. Your observer could carry out a case-study observation of students you identified who are easily distracted or those students who need challenging further to extend their thinking. You may be able to begin to unpick the causes of distractions and plan how you can develop students’ thinking during the feedback as a result of being open with your observer.

Peer observation provides a new way of approaching a problem.

It can help you to develop a fresh approach to managing a challenging group of learners or developing strategies for supporting students with specific learning needs. This could be especially effective if the observer also has experience of teaching the same class or some of the same students and can share their experiences with you.

Peer observation boosts confidence.

It provides an opportunity to work with someone who understands the daily demands of the classroom, and this can help relax you. It is also a good reminder that all colleagues have parts of their teaching that can be developed, regardless of how long they have taught or what position they hold in the school.

Peer observation encourages reflection.

Being reflective is crucial to developing your teaching and learning. Being observed gives you the opportunity to reflect, both before and after the observation, giving you the space to stop and think about how you teach. You shouldn’t just reflect on what you need to develop but also on your strengths and what good practice you should be sharing with your colleagues.

Benefits for the observer

Peer observation develops communication skills.

Being an observer gives you the opportunity to discuss teaching and learning and practise giving constructive feedback, using evidence from the observation. A teacher taking part in peer observation in a secondary school reflected on her role as the observer: “It challenged us to sit on the ‘other side of the fence’ as the observer, giving us an opportunity to feed back using this format; challenging us to be honest with our colleagues as well as highlighting our own development points.”

Peer observation helps you to reflect on your own teaching.

When observing you can pick up useful strategies and solve issues that arise in your own teaching. Also, you may teach some of the same students that are in the observation lesson. It can be enlightening to see how students react differently in other subject areas, with different groups of learners and in different classroom layouts.

“…in observing another teacher, the observer draws on her professional vision, her adapted way of seeing the field of practice, to render the observed scene intelligible. In doing so, she engages in a ‘double-seeing’ of her own classroom in comparison to the classroom that she observes.”

Benefits for the school or institution

Peer observation demonstrates a school’s commitment to professional development.

It can contribute to the development of the whole school by creating a professional learning community dedicated to improvement. By opening up the classroom and sharing strengths with each other, good practice is seen and celebrated. Importantly, areas for development are highlighted and colleagues then work together to plan next steps.

“What you do not know, indeed what you cannot know, is often more important than what you do know.”

Peer observation can improve teaching and learning in a school.

It gives colleagues the opportunity to learn from each other, with the aim of improving teaching practice and gaining new ideas. John Hattie (Hattie, Masters and Birch, 2015) notes that a shared approach to professional development has been proven to improve teacher effectiveness. If resources are available, the school could give all staff a written document containing excellent observed teaching strategies to make sure good practice is shared with everyone.

Peer observation encourages an open and sharing school culture.

It provides teachers with dedicated time to share good practice with colleagues so that they are not isolated. This helps to prevent teachers passively accepting new knowledge and only making changes to their teaching as a result of a senior leader coming in and telling them what to do. We wouldn’t want our students to approach their learning like this and the same applies to our staff!

Peer observation gives teachers the power to make changes.

When teachers feel supported to make changes to their practice they can help shape conversations about teaching and learning in a school. Effective schools make sure a teacher’s voice is heard, and encourage teachers to develop their own teaching. Teachers who talk about teaching and learning may help to influence policies set by the school.

In the video below, Teaching School Director, Kay Blayney identifies collaboration as a key benefit of peer observation. Do you agree? Which benefit most appeals to you? Which would develop your practice further?

What is the research behind peer observation?

Peer observation fits into an area of psychology called social cognitive theory. An important idea from social cognitive theory is that people can learn from taking part in social interactions and observing others.

So, by observing one of their peers teaching a lesson, the observer builds on their current knowledge and ideas for teaching. But peer observation doesn’t just increase knowledge of teaching and learning; it can also increase confidence. In their research on peer observation in higher education and schools, both Rhodes & Beneicke (2002) and Hendry & Oliver (2012) link peer observation to increasing a teacher’s self-belief (also known as self-efficacy). The observer may be inspired to try something new in their own classroom or come away from an observation feeling that what they are currently doing is in line with good-quality teaching and learning.

Another influence on teacher confidence and student outcomes is ‘collective teacher efficacy’. This is the belief that together, teachers can make a positive difference to their students. In 2017, John Hattie placed collective teacher efficacy as the most powerful influence on student achievement. If an effect size of 1 is the equivalent of advancing student achievement by two to three years, the impact of collective teacher efficacy, with an effect size of 1.57, has huge potential to develop student outcomes. Peer observation can help develop this belief, by teachers working together knowing that by improving their teaching they can encourage better student learning.

In their study on professional learning in a college in Australia, Smith and Sharmer (2017) found peer observation was an opportunity to move away from telling teachers what to do and instead allowed teachers to draw on their professional knowledge of their learners, their teaching experience, and the context within which they teach. It provides teachers with dedicated time to work together, to have conversations about their teaching and to share their expertise.

Peer observation is an excellent opportunity to observe and reflect on good teaching and learning. It is not about simply copying other people’s styles. Instead, effective teachers reflect on what they have experienced and how they can adapt it to suit their own teaching. In his book ‘Leadership for Teacher Learning’, Dylan Wiliam (2016) says teachers should adapt and modify techniques they see to make sure they work best for them. Even if these are small changes, they can have a big effect on students’ learning. Don’t be afraid of adapting approaches for your own classroom and your learners!

"…the ability of teachers to modify the techniques to make them work in their own classrooms is an important feature of any effective model of teacher development.”

Six common misconceptions about peer observation

‘Peer to peer’ is the only way to carry out an observation.

Peer observation can take place in pairs but could also involve three colleagues working together. This might involve two colleagues observing while another teaches the lesson. If you have two observers, perhaps they could focus their observation on two different students or groups of learners. Or, while one of you observes, the second one could speak to the students, but only if you agree this before the observation starts. See below for more information on alternative models of peer observation.

You should only give positive feedback.

This depends what we mean by ‘positive’. While observation must be non-judgemental, there is a risk that there could be no change in teaching if you only say ‘nice things’ about each other’s teaching without saying how you could develop. You can overcome this by carefully pairing up colleagues and making sure you trust and respect each other.

“Staff need to feel safe if they are to be honest about their teaching; and there needs to be a collegial spirit of mutual support among equals if tutors are to accept a collective responsibility for teaching within a department.”

It takes too long to carry out a peer observation cycle.

Time is always a challenge in any professional development activity, so it is essential to focus on what works. Peer observation involves working with others, and teachers may need time out of the classroom to carry out an observation. But it is flexible. If you are taking part in an observation you should consider the best times during a term to observe or be observed, which classes are best to be observed with and when there will be enough time to give feedback. By agreeing a focus for the observation beforehand, the time spent observing and giving feedback is targeted on learning, meaning you use your time more efficiently.

Colleagues should be from the same department.

Not necessarily, it depends on the purpose of the observation. If knowledge of the subject content is crucial for the focus of the observation, this may be the case. However, belonging to a different department or institution may be beneficial to learn more generally about teaching. This point is highlighted by an English teacher who had the opportunity to work with colleagues from the Languages faculty during their peer observation cycle: “This was useful in the sense that it gave us an insight into how other subject teachers approach their subjects, as well as what resources they use. Certainly, from the French lesson that I observed, I witnessed a pace and challenge that I would like to adopt within my English lessons, as well as resources to go with this.” In a study by Hammersley-Fletcher & Orsmond (2004), staff felt it benefited them to see how other disciplines approached teaching. It is also important that peer observation doesn’t become repetitive or stagnate. This is a risk if it is only ever colleagues from the same department who observe each other.

“More than one study has reported that colleagues who are too close may be unwilling to provide honest feedback about negative aspects of teaching by the observer.”

Peers who observe each other must want to develop the same part of their teaching practice.

You don’t have to both be developing the same part of your teaching. In fact, sometimes it is better for you to have different strengths. For instance, it may be that you pair up with a colleague whose strength is ‘effective use of plenaries’, which is an area you want to develop, and your strength lies in your behaviour management, which is what your colleague wants to develop. However, it is worth thinking carefully about who can support you to develop. While you are not expected to copy the exact teaching approaches of your peer, it is worthwhile thinking carefully about whose approach to teaching you feel is closest to your own. This is a good idea, as you are more likely to feel you are able to apply what you have observed your peer do when back in your own classroom.

I have to agree with the feedback from my peer.

No you don’t, but you do need to be open to receiving feedback. The feedback after an observation gives both teachers the opportunity to talk through their reflections on the lesson. It is not essential for you both to have the exact same interpretation of the events of the observation lesson. Instead, you learn from talking and making sense of what was observed (O’Leary, 2014). It is the open discussion between you that is crucial.

Imagine a colleague has one of the misconceptions above. What could you say to deal with their misconception?

Peer observation in practice

Before the observation

Peer observation should be carried out as often as possible, be confidential, and encourage all staff involved to learn from each other. For peer observation to work effectively, the focus should be driven by you (the teacher being observed). However, you need to reflect carefully when setting your own learning agenda, and you should always focus on the needs of the students (Wiliam, 2016).

Think about your own teaching practice and the needs of your students. What are your strengths? What would you like to receive feedback on? If you are unsure, who could you ask to support you to develop your observation focus?

To make sure you are thinking about the needs of your students, you may find the following points helpful as a starting point when creating your observation focus. Here are a few suggestions to get you thinking.

- How did I check that all students had made appropriate progress?

- What am I doing in my classroom to stretch my high-performing students?

- What opportunities did I provide for my students to build on their knowledge?

- How effective was my use of whole-class discussions?

- At which points in the lesson did my students have to think hard for themselves?

- Did the group activity really encourage collaboration between students?

- Were the aims of my lesson clear and were they met?

Watch the video of Teaching School Director, Kay Blayney talking about her experience of being a part of the peer observation process. What difference do you hope peer observation would make to your teaching? What difference do you hope peer observation would make to your learners?

During the observation

Recording methods

If you are the observer, your role is to record what happens in the lesson. The method you use must record the information you need for the observation focus and the feedback discussion that will follow. Think carefully about which recording method to use.

Written analysis: This is an essential part of any peer observation, whether you use it by itself or with other observation methods. Written analysis is not an open-ended document that merely reflects your thoughts. It needs to keep to agreed criteria to make sure the observation is structured and focused. Written analysis could be:

- a case study of a specific student or group of students (notes may include evidence of how they interact with other students and with the learning tasks, and how they take part in certain stages of the lesson);

- a note of strategies and techniques used by the teacher; and

- noting at least 15 questions asked by the teacher (and their responses) during the lesson. During the feedback, it may be useful to identify the type of questions asked (O’Leary, 2014).

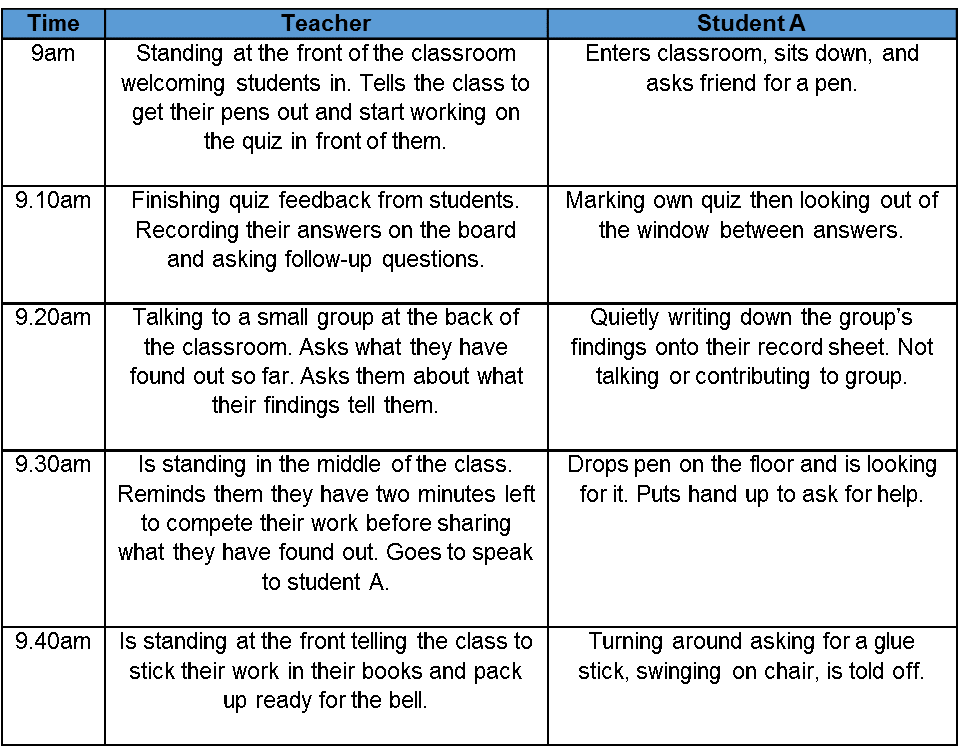

Ethnography-style observation: This type of observation records factual descriptions of what the teacher is doing and what the students are doing. You might observe the whole class or focus on specific groups of students or even just one student. Your aim is to gather as many details as possible during the observation, but not to make any judgements or comments. This recording method can be a powerful way of providing useful feedback to the teacher after the observation. It is a good way of staying neutral and putting the focus on the teacher, as it allows you to talk about specific choices the teacher made during the lesson. The table below is one example of an ethnography-style observation. At 10-minute intervals you record exactly what is happening in the classroom. The example below focuses on the actions of the teacher and one particular student (student A).

Checklists: A checklist is a useful, quick recording method of noting identified teaching and learning techniques. It could include the number of questions asked during the lesson by either the teacher or students or an agreed list of criteria to tick off when seen. It may involve a list of all the different roles a teacher takes on during the lesson, from presenter to facilitator to assessor (O’Leary, 2014). Checklists provide a snapshot of what takes places during a lesson. They can be limited in the feedback they produce, so it may be useful to add more detail where necessary to illustrate the points further.

Video camera: You may want to use a video camera to carry out an observation, as the recording can be used to form the basis of a powerful learning discussion. You can watch the recording many times, and it has the advantage of helping you to be objective about what happens in the classroom. A teacher can see how students respond to their teaching, which may be different from how the teacher thought they responded. It is a good idea for both teachers involved in the recording to agree on how they will use it to inform their conversation about feedback. It may be an idea to sit down together to watch the video to make sure your analysis of what has been filmed is impartial.

After the observation

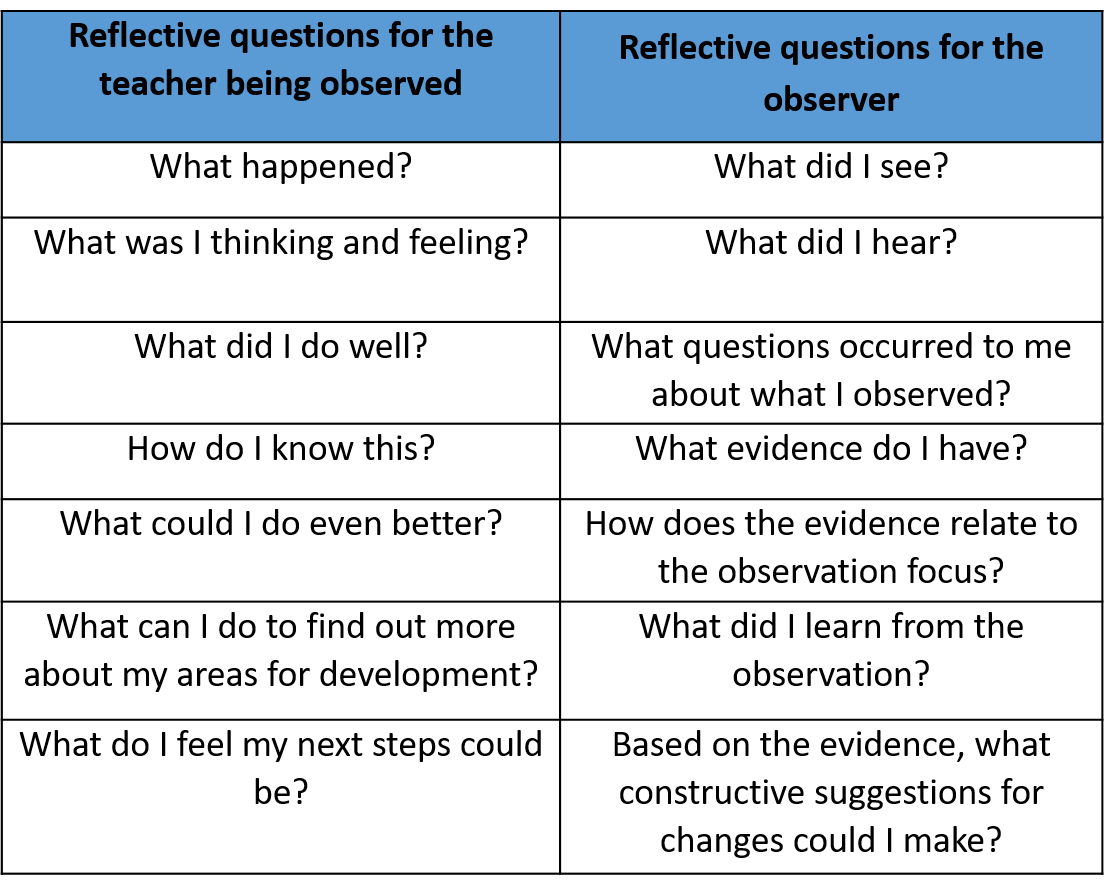

You need to prepare carefully for the discussion following the observation, as it needs to be constructive and based on mutual respect and trust. You may find the reflective questions in the table below useful. They are based on ‘Learning by doing’ by Graham Gibbs (1988) and you can use them to analyse a situation or to plan a feedback session.

Guidelines for giving feedback

- Do not feel you have to be the expert − remember you are working as peers. It may be a good idea to give the teacher you have observed a chance to comment on the lesson first. It could be useful to add what you have learnt for your own teaching practice.

- Another way to start a feedback discussion is to ask the teacher what their objectives were. This will help you to understand what the teacher was trying to achieve.

- Give honest and constructive feedback using the evidence from the observation related to the focus question. Consider planning questions beforehand to guide the discussion and use language that you both understand.

- You must make sure the feedback is non-judgemental. Focus on the act rather than the person. For instance, ‘Sarah did not look as if she was concentrating’, rather than ‘Why didn’t you challenge Sarah when she wasn’t concentrating?’

- Challenge the teacher by using open, probing questions to help them learn from and reflect on the observation. Questions beginning with ‘what’ are softer sounding than those beginning with ‘why’ such as, ‘What were you hoping to achieve when…?’ , ‘Could you have done that in a different way?’ , ‘How do you think your lesson was received by the students?’

- You might want to observe what the students do in the lesson rather than focus only on what the teacher does. This means your feedback will be focused on the actions of the students. This will help to prevent judgemental comments such as ‘You aren’t very good at leading whole-class discussion’ and instead emphasise student action, ‘I notice that several students didn’t contribute to the discussion’.

- Try to discuss solutions rather than talk about problems. Let the teacher who taught the lesson take the lead, don’t just tell them what you would do.

- Encourage a conclusion that looks for solutions, acknowledging what has been learnt by both teachers. Check that you both understand what has been discussed, using prompts such as ‘So are we saying that..?’ or ‘My understanding of your planned way forward is….’

- Plan the next steps through drawing up ideas for a manageable action plan. It is important to focus only on what is worth changing rather than trying to change everything.

As the observed teacher receiving feedback

- Be open to the feedback and give yourself plenty of thinking time before responding to your observer.

- Feel free to explain your approach and how the lesson felt from your point of view.

- Make notes if it helps you to identify key points for further discussion. You can use these to plan future professional development.

- Remember to discuss what the observer has learned from observing you, as developing their teaching practice is also an important part of the process.

- Plan the next steps by drawing up ideas for an agreed, manageable action plan. Don’t try to change everything. It is important that you have an action plan that you are responsible for and feel you can put in place successfully.

Alternative models of peer observation

Lesson study

This is a model of teacher-led research, which originated in Japan and is used particularly in Maths and Science. A small group of teachers work together to target an area for development in their students’ learning. They then work together to plan the observation lesson. Detailed information is collected during the observation and forms the basis of feedback on how the lesson could be improved (Wiliam, 2016). The diagram below outlines the lesson study cycle.

Watch the video below of Vice Principal Dave Goode describing his school’s approach to lesson study. Which of the differences made by lesson study are most relevant to your students and school?

It is common for teachers involved in lesson study to spend six months on developing a single lesson, so this model may not be practical for all teachers in this format (Wiliam, 2016). However, you might want to try out a model of observation that is inspired by lesson study, adapting it to suit your own situation. The video gives us an example of this.

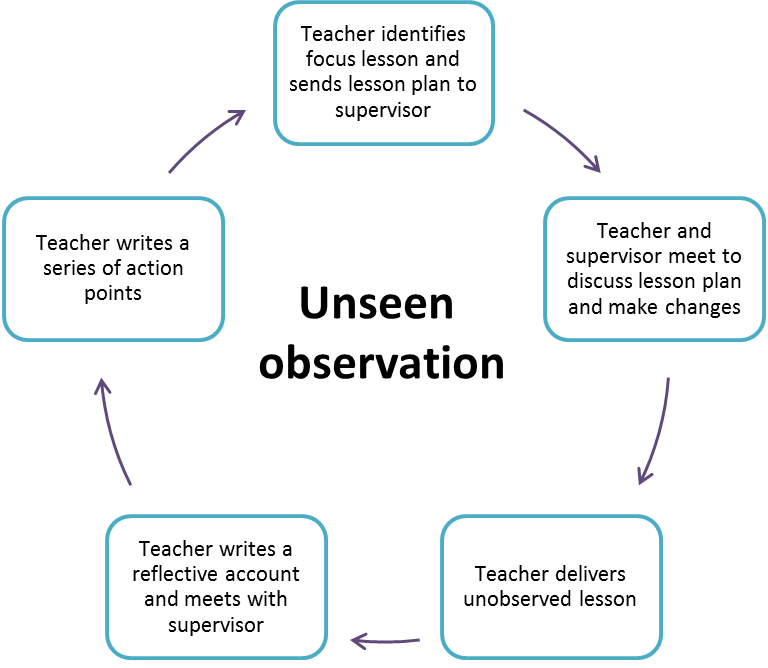

Unseen observation

The main difference between an unseen observation and peer observation is that an unseen observation doesn’t actually involve your peer observing you teach a lesson. (See the diagram below for a detailed outline.) Instead, it involves two colleagues discussing the plan for the focus lesson in a meeting beforehand and the teacher reflecting after they have taught the lesson. In an unseen observation, the ‘observer’ is known as the supervisor. While this may sound authoritative, it is not the case. Their role is to ask questions that encourage reflection and self-analysis. This model emphasises the teacher as an individual and removes the anxiety that can come from being observed.

“When someone new comes into the classroom to observe, then the very presence of an additional adult who is not normally present may influence what happens.”

Bear in mind that the supervisor will only hear one view of the lesson and has to rely entirely on the honesty and accuracy of their colleague’s account of it (O’Leary, 2014). This approach to observation focuses on teachers taking responsibility for their own professional growth, even when nobody is watching.

We have introduced peer observation, lesson study and unseen observation in this guide. Which model would best suit the needs of your learners, colleagues and school? It may be useful to consider the benefits and limitations of each model to help you make a decision.

Peer observation checklist for teachers

Do I have the support of my senior leadership team?

Peer observation may be an initiative that has come from the senior team. However, it may be something that you and some colleagues want to try out as a ‘stand-alone’ process. You should discuss it with managers to make sure that they are supportive, that it doesn’t clash with any other professional development initiatives, and that any time taken out of lessons is fully supported by the leadership team.

Have I reflected on my own teaching to identify areas where I can improve?

While a peer can support you to think about an observation focus, it really should come from the teacher who is being observed. The inspiration for the observation focus may come from a number of sources. It might have come from feedback from a more experienced colleague, something you want to try out from a training course you attended, or maybe from having observed a colleague previously.

Who should I work with?

If there is an opportunity to decide who to work with, think carefully about which colleague you feel you could learn the most from. You may want to pair up with someone who approaches teaching in a similar way to you so you can imagine how to apply what you see in your own classroom. It may be that your school recommends pairings based on individual strengths. Either way, it should be a teacher you feel you can have an honest and open discussion with.

Reflect on your own experiences of observations.

You have probably experienced observations before, either as an observer or as the teacher being observed. Think about what you liked about the process and what you didn’t like. What did you find useful, and what would you do differently? Giving yourself the time to reflect on your own past experiences will help you to refine the process and make sure it is works for you and helps you to develop.

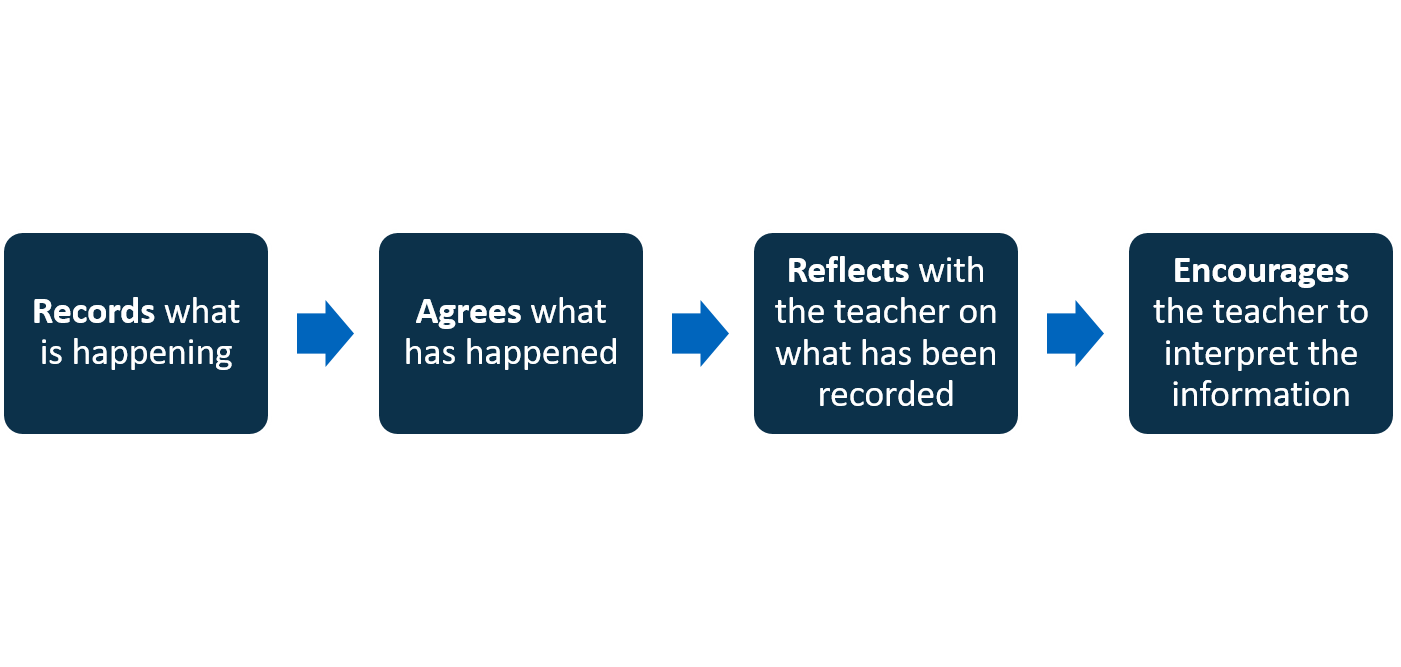

As the observer, do I know what to do?

Not every teacher involved with peer observation will have had the chance to observe a colleague before – this is a process of development for everyone involved! Be open to feedback and take the time to reflect on your role as the observer. Bear in mind that you are not there to be the expert. The diagram below has been adapted from Tilstone (1998) and could be a starting point to clarify your role as an observer.

How can I make sure the process helps development?

It is difficult to avoid forming opinions of the teaching that you are observing, as forming opinions is a part of human behaviour. One way to avoid this during the observation is to record factual descriptions of what happens during the lesson, which you can then use as evidence during feedback. During this feedback, work with your peer to help them interpret the evidence for themselves, even if it is not the same interpretation you have.

“…professional development must include opportunities for active interpretive processes that examine the complex contexts of classrooms and schools.”

Next steps for the leadership team

Read about peer observation.

There are many articles and blogs freely available online which cover different aspects of peer observation. These cover topics from teachers’ own experiences of taking part in peer observation to schools reflecting on how they put observation into practice and sharing their top tips. While you are reading, think about any similarities to you and your school and how you can apply these to your own peer observation. See ‘Want to know more?’ below.

Talk to colleagues.

You may have colleagues who have taken part in peer observation. By talking to them you can get advice on how to get the most out of the process, whether they encountered any problems or if they would approach any of it differently. Using the past experiences of your colleagues is a good way to learn about successes as well as any pitfalls to avoid.

Establish and communicate the purpose of peer observation.

Make sure all staff are clear on why they are taking part in peer observation. Be prepared to answer any questions or concerns they may have. If staff have only experienced graded, judgemental observations, they might be nervous about taking part. Reassure them that observation is there to support their professional development – it is not about grading teachers. You could use peer observation as evidence of a teacher having taken part in professional development. It then becomes a way of recognising that teachers have taken part in professional development, rather than a way of making a judgement about their teaching.

Identify the needs of your learners.

In some schools, it may be valuable for teachers to focus on what they feel they need to develop in their teaching practice. But it is also just as appropriate for the school to suggest a theme for staff to focus their observations on, based on learners’ needs. You could offer a number of themes for staff to choose from, based on areas of teaching and learning the school has identified as needing to develop, such as ‘inclusive education’ or ‘effective classroom talk’. You might also want to think about whether or not you will need to prepare your students for their teachers being involved in peer observation. If having more than one member of staff in the classroom is unusual, explaining why they are there may reassure students and highlight that their teachers are learning too!

Think about the culture of your school.

It is likely that you will have staff in your school who have come from a range of teaching backgrounds and schools, and so they may have very different experiences of observations. You may find some teachers do not like to be observed at all. This process may be different for them; it may be about getting them used to having another member of staff in their classroom and becoming comfortable with this.

Want to know more?

Here is a list of interesting books and articles on the topics we have looked at.

Glossary

Collective teacher efficacy

The collective belief that together, teachers have the ability to make a positive difference to students’ achievement.

Critical friend

Someone who is encouraging, supportive and truthful and provides honest, constructive feedback that may be uncomfortable or difficult to hear.

Criticism

Making a judgement about observed practice in which you give your opinion of perceived faults and mistakes.

Critique

A critical analysis and assessment of observed practice in which you offer your opinion about a teacher’s strengths and areas they can develop.

Feedback

Constructive information about how the observed teacher is doing in trying to reach a goal or look at an issue.

Open question

A question that can’t be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or any other one-word response.

Self-efficacy

The belief we have about our ability to succeed in specific situations and to accomplish tasks.

Social cognitive theory

The view that people can learn by observing and interacting with others in social situations.

Teacher self-efficacy

A teacher’s level of confidence in their belief that they are able to lead their students to success.